Far be it from me to doubt Steven Spielberg’s understanding of Hollywood, but his widely-reported prediction of a future in which we could shift to a system in which viewers pay much higher prices for blockbuster releases and pretty much everything else goes to pay-TV (or has lower ticket prices) seems distinctly unconvincing. More the stuff of rather typical industry doom-monger hype than any real analysis of likely future scenarios, I think.

Spielberg’s suggestion, during the opening of a new facility at USC, is premised on a situation in which a bunch of expensive blockbusters fail, bringing down the current release system. That’s a large assumption in itself. However much it might be disliked by many, the current studio blockbuster-led regime has proved consistently reliable for a few decades now and we shouldn’t expect it go to away anytime soon, whatever adjustments might come in the handling of post-theatrical release. Every now and then there’s a dry blockbuster season, provoking predictions of demise. But so far this has always been followed by a bounce-back, typically characterised by another round of non-inflation-adjusted ‘record-breaking’ openings, etc.

The idea that ‘Going to the movies is going to cost you 50 bucks, maybe 100. Maybe 150’ seems, frankly, somewhat nonsensical. This is based on a suggested parallel with high-end stage theatre or sporting events. But such a parallel doesn’t work and misses the fundamental nature of the blockbuster business, which is an appeal to very large numbers and especially to younger people who’d never be able to afford such rates. That’s nothing like the situation with, say, Broadway theatre or live sporting events with limited capacity for attendance. Does anyone seriously think Hollywood is going to jeopardise its ability to reach its core audience? The Guardian newspaper in the UK suggests that there are already signs of this kind of change, citing a posh, upmarket Odeon in London – but this seems like a red herring. Sure, places like London will have such venues, with extras for the wealthy who can afford them, but these are niche theatres that are in no way a viable alternative to those which serve the main audience.

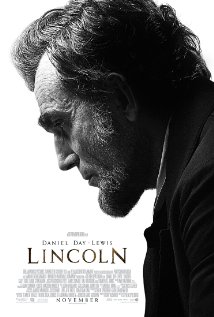

The flip side of Spielberg’s comments relate to the fate of less commercial fare such as his recent Lincoln. It struggled to get theatrical release, he says. I’m somewhat doubtful about that, but then Spielberg is arguably in an exceptional situation as far as being able to get funding and release for almost anything he wants to do. The real question here is the space that exists in contemporary Hollywood for less-obviously commercial material, what’s historically been known as the ‘quality’ film (a term that requires lots of unpacking, of course). This is what I’m currently writing about, and it’s striking how similarly hyperbolic is much of the commentary on these kinds of films, along with blockbusters and ‘the fate of cinema as we know it’ more generally.

The ‘death of serious/adult/quality films’ in Hollywood is a subject of regular reporting (as is the suggestion that ‘the only place’ to find such material these days is on pay-TV). As is an expression of amazement every time one or a few such films does appear – or, especially, if it/they do well or relatively well commercially. There’s definite hype-cycle here: it’s dead; wow, it’s come back to life. The less headline-friendly reality is that a limited space for such films has always existed within the studio realm and continues to do so, even within a system dominated by franchise-oriented blockbuster production. The nature and degree of this space (limited), and factors that might explain its existence, are what I’m currently writing about.

So, this intervention by Spielberg seems rather familiar. I’d suggest not taking it at face value, but as a manifestation of a particular kind of rhetoric that’s typical of Hollywood. Part of this, more generally, involves creating an impression of an industry in or barely short of being in crisis – and, thus, one that shouldn’t be subject to things like regulatory intervention. Can’t help also reading a bit of personal bitterness in some of the comments (particularly the contribution from George Lucas and reference to the limited release enjoyed by Red Tails; could that simply have been because, beyond Star Wars, most of what he’s done has not exactly set the box office alight?).

How should academics respond to these kinds of claims? My view is not to play the speculation game on these terms, which has a tendency to lead to large-scale over-statement and hype of its own kind (see anything with a title that contains phrases such as ‘the end of cinema as we know it’). Better to seek to situate the nature of such comments within more familiar discourses within the industry and to measure past examples against the realities that actually exist or followed. We shouldn’t rule out possibilities for future change, of course, but these tend to be evolutionary rather than revolutionary in kind and degree. That doesn’t make such good headlines but is the stuff of the kind proper sober analysis that’s needed if we’re really to understand the way the business works.